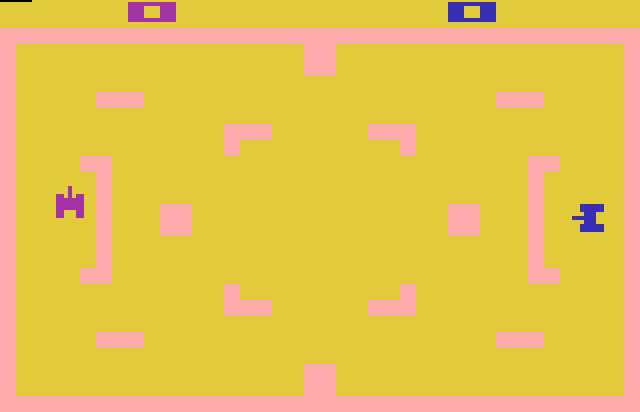

Combat

The Game That Started Everything

Larry Kaplan had a problem. It was 1977, and Atari needed a pack-in game for their new Video Computer System—something that would demonstrate the console’s capabilities without overshadowing the games people would buy separately. “They wanted impressive but not too impressive,” Kaplan later recalled. “Something that showed off the hardware without making people think they didn’t need anything else.”

But Kaplan had his own agenda. Fresh from Fairchild Semiconductor’s engineering team, he’d watched the Channel F struggle because its pack-in game was too simple. He believed the VCS launch title needed to be more ambitious—not just a tech demo, but a legitimate game that people would actually want to play. “I knew this cartridge would sit in millions of living rooms,” he explained in a 1983 interview. “It needed to have staying power.”

What emerged was Combat—a seemingly simple tank and plane game that became the foundation of competitive gaming in American homes. It wasn’t the flashiest game Atari would release, but it was arguably the most important: the game that taught an entire generation how to play video games together.

A Military Obsession Meets Silicon Valley

Kaplan’s background shaped Combat in ways that weren’t immediately obvious. Unlike many programmers who came from computer science backgrounds, Kaplan had grown up fascinated by military history and strategy. His father had served in World War II, and young Larry spent hours studying tactical maneuvers and equipment specifications. “I could tell you the armor thickness on a Sherman tank before I could solve quadratic equations,” he joked years later.

This military obsession collided perfectly with the cultural moment of 1977. The Vietnam War had ended just two years earlier, but military themes still dominated popular culture. Movies like Midway and A Bridge Too Far packed theaters. Model tank kits lined hobby store shelves. Americans were processing complex feelings about warfare through entertainment—not glorifying it exactly, but not entirely rejecting it either.

Kaplan saw an opportunity. The VCS’s hardware—with its ability to display two independent player sprites and two missile sprites—mapped perfectly onto military scenarios. Tanks. Planes. Projectiles. The hardware seemed designed for combat simulation, even if that wasn’t Atari’s original intention.

“The VCS gave me exactly what I needed: two players, two bullets. That’s the essence of combat—two opponents, limited ammunition, tactical decisions. Everything else is just details.”

—Larry Kaplan, Electronic Games Magazine, 1981

The Creative Process: Twenty-Seven Variations on a Theme

Here’s where Kaplan’s genius became apparent. Rather than creating one perfect game, he created twenty-seven variations—a decision that seemed excessive to Atari management but proved revolutionary for home gaming.

The Tank Combat Variations: Kaplan started with tank battles because they were easiest to program and most familiar to players. But he didn’t stop at simple tank-versus-tank. He added invisible tanks (where players had to track opponent positions mentally). He created ricocheting shells that bounced off walls. He programmed tank-pong, where the goal wasn’t destruction but getting a shell past your opponent.

“Each variation taught players something new,” Kaplan explained. “Invisible tanks taught spatial awareness. Ricocheting shells taught geometry. Tank-pong taught timing and prediction. I wanted the game to have educational value without feeling like homework.”

The Biplane Variations: The biplane modes were technically more ambitious. Making planes move smoothly while rotating was a significant programming challenge on the VCS. Kaplan solved it by limiting rotation angles and carefully controlling acceleration. “I couldn’t do true 360-degree rotation,” he admitted. “But I could do enough angles that it felt right. Sometimes ‘feels right’ is more important than ‘technically perfect.'”

The biplane variations also introduced a crucial innovation: cloud cover. By adding visual obstacles that bullets couldn’t penetrate, Kaplan created natural cover that rewarded tactical play. This wasn’t just a visual flourish—it fundamentally changed strategy. Players had to balance offensive positioning against defensive protection.

The Jet Fighter Variations: The jet modes were Kaplan’s attempt to push the hardware harder. Faster movement, guided missiles, different acceleration curves. “The jets were for experienced players,” he said. “Once you’d mastered tanks and biplanes, the jets offered something more challenging.”

But here’s what’s remarkable: Kaplan didn’t just make jets “faster biplanes.” He changed the acceleration model, the turning radius, the bullet speed. Each vehicle type had distinct physics that required different skills. Modern game designers call this “mechanical depth”—Kaplan was inventing it in 1977.

The Publisher’s Vision: Atari’s Smart Gamble

Atari’s decision to pack Combat with every VCS wasn’t just about saving costs—it was a strategic masterstroke that reflected Nolan Bushnell’s understanding of social gaming. Bushnell had built Atari’s arcade business on competitive two-player games like Pong. He knew that gaming’s future wasn’t solitary play—it was about bringing people together.

“Nolan kept saying ‘water cooler moments,'” Kaplan remembered. “He wanted games people would talk about at work the next day. Combat was designed for that. When someone discovered the invisible tank trick or figured out the perfect ricochet angle, they’d tell their friends.”

This approach influenced the game’s difficulty curve. Combat started accessible (simple tank battles) but hid complexity for those who explored. Variation 1 could be mastered in minutes. Variation 27 (jet fighter with guided missiles) required genuine skill. This range meant Combat could grow with its players—something revolutionary for 1977.

The marketing challenge was explaining twenty-seven variations without overwhelming potential buyers. Atari’s solution was brilliant: emphasize the variety as value. “27 games in one cartridge!” became the pitch. It positioned the VCS as offering more content than competitors, even though many variations were subtle tweaks rather than entirely new games.

The Cultural Impact: Competitive Gaming Enters the Home

Combat’s release in September 1977 coincided with the VCS launch, and its impact was immediate. Early reviews focused on the graphics and variety, but something more significant was happening in living rooms across America: families were discovering competitive gaming.

“Before Combat, home gaming meant playing against the TV,” explained Chris Crawford, game designer and early industry analyst. “Combat made gaming social. It brought the arcade’s competitive energy into homes. That psychological shift was enormous.”

Players developed their own meta-strategies. Some families banned certain variations as “too cheap.” Others created house rules—no camping in corners, no spawn-killing. These negotiations around fairness and fun became part of the Combat experience, teaching players to think critically about game balance.

Contemporary Reception: Video magazine called Combat “the most complete game yet seen on a home system,” while Electronic Games praised its “deceptive depth.” Sales figures told the story: every VCS came with Combat, but remarkably, players kept their Combat cartridges inserted longer than many purchased games. It had become the default activity—the gaming equivalent of a deck of cards.

Developer Influence: Combat’s structure influenced countless games. The “multiple variations on a core mechanic” approach became standard for early VCS titles. Games like Air-Sea Battle, Video Olympics, and Outlaw all followed Combat’s template of offering numerous gameplay variants. Even later games like Warlords and Breakout adopted this “variety pack” approach.

Kaplan’s Reflection: The Game That Got Away

Larry Kaplan’s relationship with Combat was complicated. On one hand, it was a massive success—the pack-in game for the best-selling console of its generation. On the other hand, he received no royalties and minimal credit. Atari’s policy at the time didn’t credit individual programmers, treating games as corporate products rather than artistic works.

“It bothered me,” Kaplan admitted years later. “Not the money—though that would’ve been nice—but the anonymity. I’d created something millions of people played, and nobody knew my name. That’s what drove me to leave Atari and co-found Activision.”

This frustration had industry-wide implications. Kaplan, along with David Crane, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead, left Atari in 1979 specifically because they wanted credit and compensation for their creative work. Activision’s founding—directly motivated by the Combat experience—changed the industry forever, establishing the principle that programmers deserved recognition as creators.

“Combat was the last game I made where I was okay being anonymous,” Kaplan reflected. “After seeing millions of people play something I created, I knew I needed my name on my work. That realization was worth more than royalties.”

The Ripple Effect: How Combat Shaped an Industry

Combat’s influence extended far beyond its immediate success. It established several principles that became fundamental to gaming:

Local Multiplayer as Core Feature: Combat proved that competitive local multiplayer could be a system-seller. This insight drove console design for decades. The Nintendo Entertainment System’s standard two-controller setup, the PlayStation’s four controller ports, even modern systems’ emphasis on couch co-op—all trace back to Combat’s success.

Variations as Content: The twenty-seven variation structure influenced game design philosophy. Developers realized that creating multiple rulesets for the same core mechanics could provide depth without requiring entirely new graphics or code. This thinking appears in everything from Street Fighter II’s character variations to modern roguelikes’ modifier systems.

Pack-In Games as Teaching Tools: Combat established that pack-in games should be tutorials disguised as entertainment. Its difficulty progression—from simple tanks to complex jets—taught players how to use controllers and think spatially. This educational philosophy influenced Super Mario Bros. (NES), Wii Sports (Wii), and Astro’s Playroom (PS5).

Competitive Balance Through Asymmetry: Some Combat variations featured asymmetric gameplay—one player had guided missiles while the other had faster movement. This early exploration of asymmetric balance influenced countless competitive games, from Left 4 Dead’s survivor/infected dynamic to Evolve’s hunter/monster gameplay.

The Contemporary Perspective: Lessons in Elegant Design

Modern game designers studying Combat are often struck by its economy of design. With minimal graphics, simple rules, and limited inputs, Kaplan created genuinely deep gameplay. This lesson resonates in today’s indie gaming scene.

“When I was designing TowerFall,” explained Matt Thorson (creator of TowerFall and Celeste), “I kept Combat in mind. How do you create competitive depth with just a few mechanics? Combat’s answer was variations and physics. That principle—create a solid foundation, then explore its possibilities—guided all of TowerFall’s design.”

The invisible tank variation deserves special recognition for inventing “fog of war” gameplay in video games. This mechanic—where players track opponents through inference rather than direct observation—became fundamental to strategy games. Combat did it in 1977 with two tanks and zero UI elements.

Modern competitive games also echo Combat’s understanding of match length. Most Combat variations resolved quickly—under five minutes. This made losing tolerable and winning satisfying without requiring huge time investments. Compare this to modern competitive games like Rocket League or Brawlhalla, which also feature short matches optimized for “one more game” psychology.

However, Combat also reveals limitations of its era. Its variations, while numerous, mostly tweaked physics and rules rather than fundamentally reimagining gameplay. Modern developers might create twenty-seven entirely different game modes rather than twenty-seven variations on tank combat. But this criticism misses the point: in 1977, the concept of “variations” itself was innovative.

The Verdict

Combat doesn’t dazzle with technical fireworks or narrative ambition. Instead, it perfected something more valuable: the social dynamics of competitive play. Larry Kaplan understood that gaming’s future wasn’t just about what happened on screen—it was about what happened between players.

Innovation Rating: 4/5 Breakthroughs

- Technical Achievement: Solid execution that pushed the VCS’s early capabilities, particularly in sprite rotation and physics variation

- Design Innovation: Revolutionary variation system and asymmetric competitive balance; invented fog-of-war mechanics in the invisible tank mode

- Historical Impact: Established local multiplayer as essential feature; directly inspired Activision’s founding; created template for pack-in games as teaching tools

- Modern Relevance: Foundational principles for competitive game design; elegant demonstration of depth through simplicity; case study in physics-based gameplay variation

Bottom Line: Combat was the right game at the right time—a pack-in title that defined what home gaming could be. While later games would surpass its technical achievements, none matched its cultural impact as the game that taught America how to play together. Every local multiplayer session, every “best two out of three” match, every argument about fair play traces back to 1977, when Larry Kaplan’s military obsession met Atari’s social vision and created competitive gaming’s foundation.

In an industry obsessed with innovation, Combat reminds us that sometimes the most important breakthroughs aren’t about doing something new—they’re about doing something essential so well that it becomes invisible. Everyone knows how to play competitive games now. Combat taught them how.